Introduction to UNESCO – some background information, what becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site involves and the pros and cons of being inscribed

Often in our worldly travels we come across a UNESCO World Heritage Site (WHS). Some we visit deliberately, and others just happen to be close to something else that has drawn us to a particular location. We keep a record of what WHSs we’ve surveyed and, astonishingly, we’ve almost clocked up 30% (318, jointly) of the 1,121 sites listed (as of early 2020). You can see details of all the UNESCO sites we’ve visited here.

It occurred to us that we’ve never really looked into what constitutes a World Heritage Site – what are the criteria, what is the submission process, and, most importantly, what are the pros and cons of becoming a WHS? With that in mind, we’ve put together a short backgrounder and some personal observations.

What is a UNESCO World Heritage Site?

In simple terms and straight from the horse’s mouth, a UNESCO World Heritage Site is a landmark or area, selected by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for having cultural, historical, scientific or other form of significance, which is legally protected by international treaties.’

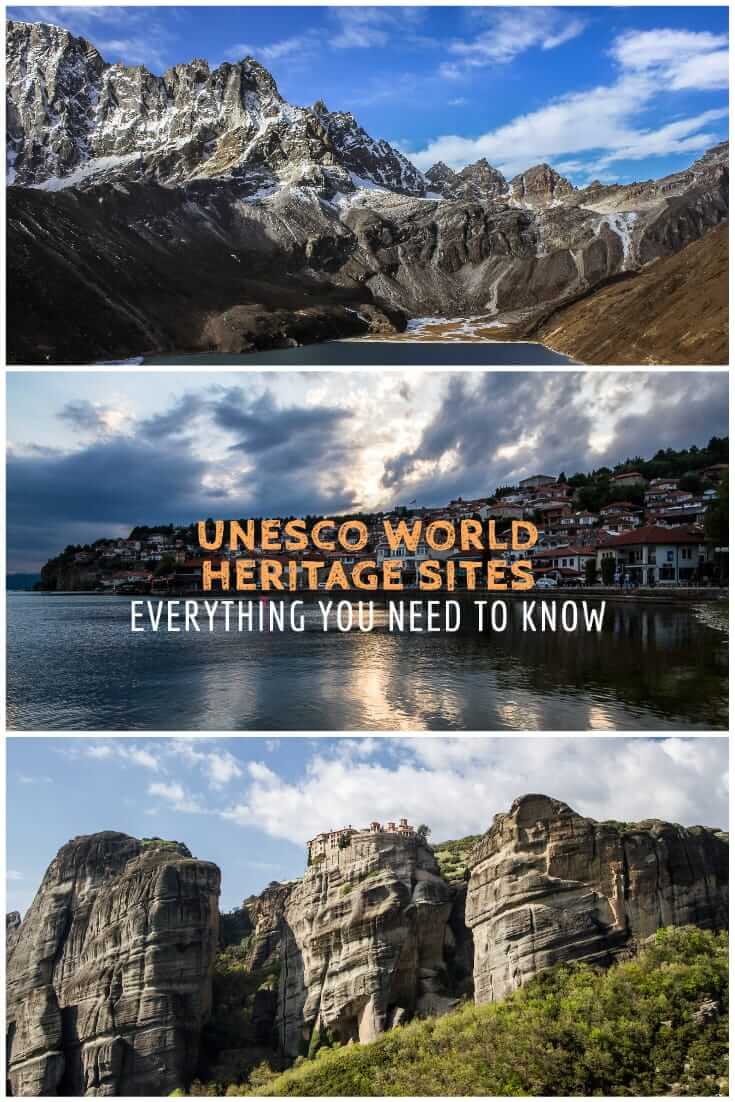

Varlaam Monastery at Meteora in Greece

Varlaam Monastery at Meteora in Greece

When did the World Heritage Sites programme start?

The construction of Egypt’s Aswan High Dam in the 1950s highlighted the need to preserve ancient treasures and the resulting international effort culminated in the formation of the UNESCO Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage in 1975. Nowadays, the committee is simply named the UNESCO World Heritage Committee.

How many World Heritage Sites are there?

As of August 2022, there are 1,154 sites, 897 designated as cultural, 218 natural, and 39 mixed. These are found in 167 nations or State Parties (countries that have adhered to the World Heritage Convention, including the non-member state of the Holy See).

What does it take to become a World Heritage Site?

To quote from Wikipedia’s WHS article, ‘To be selected, a World Heritage Site must be an already-classified landmark, unique in some respect as a geographically and historically identifiable place having special cultural or physical significance (such as an ancient ruin or historical structure, building, city, complex, desert, forest, island, lake, monument, mountain, or wilderness area). It may signify a remarkable accomplishment of humanity, and serve as evidence of our intellectual history on the planet.’

Just because a site has WHS status does not automatically make it a must-visit attraction. Occasionally we visit a place and say to ourselves, ‘Why is this UNESCO approved?’ but we have to remind ourselves it’s sometimes about cultural preservation and archaeological significance. An example that comes to mind is Ban Chiang Archaeological Site in Thailand. We were particularly underwhelmed when we visited in November 2017: there was a good museum and an excavated burial ground but not much else. Maybe the site has been much improved since then?

Another example is the chain of survey triangulations known as the Struve Geodetic Arc. We have seen the monument which marks its starting point at Hammerfest in Norway and it’s really a case of ‘You’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all!’

Bryggen in Bergen, one of Norway’s more colourful UNESCO World Heritage Sites

Bryggen in Bergen, one of Norway’s more colourful UNESCO World Heritage Sites

What is the submission process?

A country wishing to submit a site for WHS consideration must first create a national Tentative List of sites. The Tentative List may contain more than one possible site but only one site on the list will go forward per year to UNESCO for consideration. Once a site has been identified by a local preservation group or national committee, a document consisting of a narrative, proof of authenticity and integrity, and a management plan is prepared by a team consisting of a project coordinator plus interested parties such as site owners, financial backers and consultants. When ready, this document is added to the Tentative List and the country then decides which site will be submitted as a Nomination Proposal to UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee.

The World Heritage Committee meets annually for around ten days (late June/early July) in a different host country (scheduled to be Fuzhou, China in 2020) to decide the final selection for that year’s additions. In 2019, there were 36 nominations from which 29 new sites were inscribed. The committee also reviews the ‘List of World Heritage Sites in Danger’ and the current state of some sites already on the list. For example, at various times this century, the UNESCO committee has put pressure on the Ecuadorian government to put tighter visitor restrictions in place for the Galapagos islands as a result of over-tourism (which they don’t blame on UNESCO listing). Illegal fishing, the spread of alien species, illegal immigration, rapid population growth, increased risk of fire, and poor governance – these, and other factors have all been cited as features and happenings that could destroy the unique status of the Galapagos islands.

The committee also has the power to strip sites of their WHS status but, so far, only two places have lost their award. Oman’s Arabian Oryx Sanctuary was delisted in 2007 after poaching and habitat degradation nearly wiped out the oryx population, and Germany’s Dresden Elbe Valley was removed in 2009 when the Waldschlösschen Bridge was built, bisecting the valley.

The ancient capital and Buddhist temple city, Bagan, in Myanmar, fought for twenty-four years for UNESCO recognition with the award finally granted in 2019. One reason cited for earlier rejections was Myanmar’s 1995 military junta’s reluctance to follow advice on restoration, but the transition away from military rule in 2011 resulted in a more sympathetic approach to UNESCO’s advice and, finally, WHS recognition.

Temples of Bagan, Myanmar

Temples of Bagan, Myanmar

How much does it cost to achieve UNESCO recognition?

The hard work, and therefore the cost, is in preparing the document containing the background, proof of authenticity and management plan to be placed in the country’s Tentative List. This document can take many years to prepare and follows guidelines created by UNESCO. There is no submission charge when presented to UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee.

What’s the good news?

There are normally three reasons why achieving WHS status is good news. The first, and most obvious one, is more revenue from increased visitor numbers. The income will help fund the management and preservation of the site and allow improvements to the support infrastructure such as road or rail access. It can also be argued that some local residents will benefit from the need to provide accommodation (hotels, B&Bs, hostels), food and beverage (restaurants, cafes, bars), shops (general stores, souvenir shops), and transport (taxi, cycle hire). These benefits will apply to those who provide these services but may have little impact on the lives of those who are not involved in the tourist-support sector. As an example, in 2019, foreign visitors to Angkor Wat produced gross ticket sales revenue of $99 million. Other than potential job creation at the site itself, the amount of money that gets put back into the local community is unknown. Certainly, most local people (who don’t work in tourism) who we’ve spoken to have said they didn’t feel any benefit.

One place you could argue has benefited is Ohrid (listed under Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Ohrid region) in North Macedonia. As the listing is for a town rather than say, just a monument, there has been a general increase in the prosperity and living standards of the town’s inhabitants but, have those visitor numbers increased because of UNESCO status or because of the rise in global travel and low-cost flights? This is a chicken and egg question. Which factor is the cause and which factor is the effect? It’s hard to say.

Church of St. John at Kaneo in Ohrid, Macedonia

Church of St. John at Kaneo in Ohrid, Macedonia

That said, it is generally agreed that UNESCO status does raise a country’s tourism profile and is helpful for marketing a destination.

The second reason cited is that WHS increases visibility and attractiveness to other funding organisations such as conservation, heritage or local community. The UK’s prehistoric monument, Stonehenge, is a good example of this. The preservation and management of this WHS is funded by a consortium consisting of English Heritage, Historic England, National Trust, Wiltshire Council and Natural England.

And finally, the third reason is that there are more subjective benefits such as improvements to a country’s touristic brand image, local and national, civic pride, regeneration (re-development) and education. Currently, Italy has 55 World Heritage Sites, a number equalled only by China. It could be argued that Italy attracts more than its fair share of tourists simply because of the high incidence of interesting historical sites available and easily reachable in a relatively small country.

What’s the bad news?

To counteract the good news, there are three reasons why achieving WHS status carries bad news. The first is the adverse impact of increased tourism (damage to the site, insufficient infrastructure, impact on indigenous inhabitants/local residents). The early exploitation of the Galapagos Islands is a good example of this and of the power of UNESCO to control the damage.

Cambodia’s temples of Angkor are a prime example of over-tourism, whether or not UNESCO status is to blame (personally, we think it’s more likely to be the result of the ‘everyone can fly’ effects of low-cost carriers in the region). In 2019, Chinese tourists accounted for almost 40% of visitors to Angkor. We suspect this is because of the increased ease and cost of travel and not because they suddenly wanted to visit the region’s UNESCO sites.

Hoi An in Vietnam is another example of an overtouristed destination. Local residents have been forced out of the town centre because they can no longer afford to live there due to increased rents. Property and land owners know that people looking to invest in restaurants, hotels, and other tourist attractions can pay more.

The second bad-news reason is the costly preparation of the initial proposal to be added to the country’s Tentative List. This puts poorer countries at a disadvantage and can lead to under-representation – more submissions increase the cost of preparing the necessary submission documents. There’s also the question of whether developing countries can afford to put together a submission and whether ethically they should spend government funds doing so.

Finally, the third reason is the possible lengthy approval/rejection process. The minimum time for a Nomination Proposal to be fully processed is eighteen months but that time can stretch out to many years depending on how many iterations of the proposal are required by UNESCO.

In summary, does addition to the WHS list necessarily guarantee benefits? Not all UNESCO sites are swamped with tourists. Hattusa in Turkey, and Dougga in Tunisia are examples of archaeological sites that we’ve visited and had almost to ourselves. But, yes, in general it’s fair to say the benefits outweigh the disadvantages and its intrinsic value in preserving our heritage for future generations is priceless.

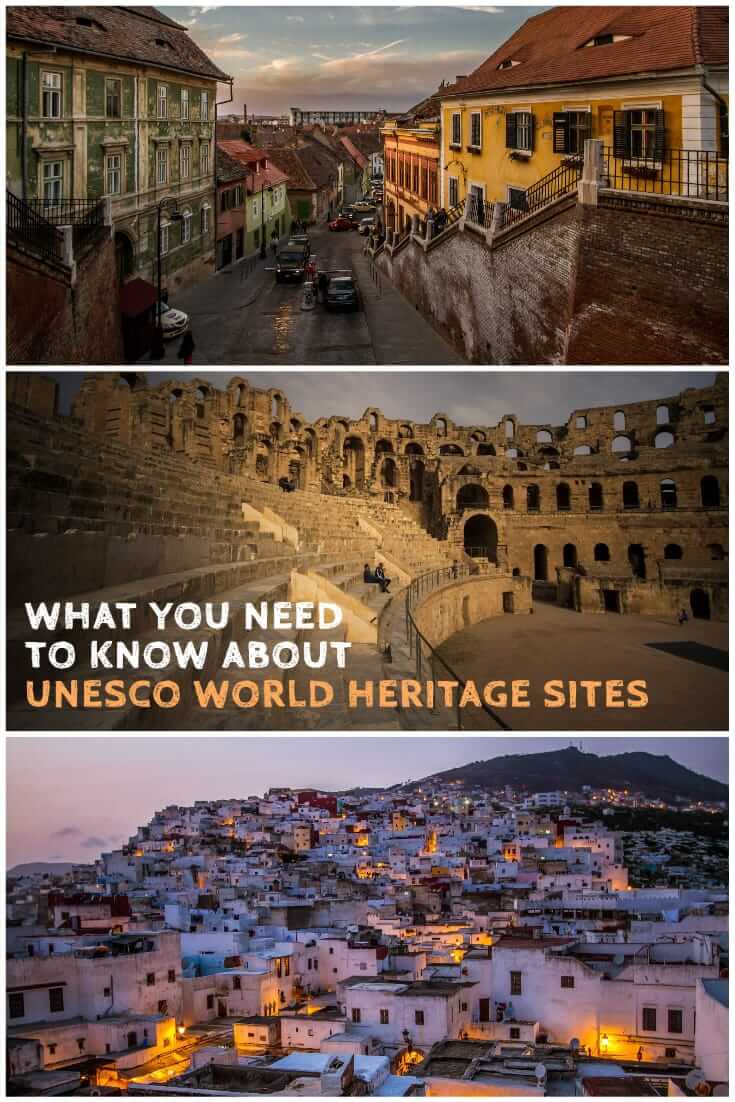

The Capitol, Dougga in Tunisia

The Capitol, Dougga in Tunisia

Footnote. Chiang Mai’s UNESCO submission

We spend a lot of time in Chiang Mai in Thailand. We enjoy the city and use it as an Asian base when we’re not travelling. In 2015, Monuments, Sites and Cultural Landscape of Chiang Mai, Capital of Lanna was added to Thailand’s Tentative List. The proposal, which also includes the nearby sacred mountain of Doi Suthep within the Doi Suthep-Pui National Park, is targeted for submission to UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee in 2022. It will be interesting to follow the application and, assuming it is eventually accepted, observe any changes in either visible signs of increased preservation efforts of Chiang Mai’s historical sites, or in the number of visitors to the city which some say is already showing signs of over-tourism.

We wish Chiang Mai luck in its application.

Wat Chedi Luang in Chiang Mai, currently on the UNESCO Tentative List

Wat Chedi Luang in Chiang Mai, currently on the UNESCO Tentative List

IF YOU ENJOYED READING ABOUT WHAT IT TAKES TO BECOME A UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE SITE AND THE PROS AND CONS OF BEING INSCRIBED AS ONE, PLEASE SHARE THIS POST…

Your story is so interesting! Can u please tell me more?