And other remnants from Jermuk’s Soviet past (with a map of locations)

The mountain spa town of Jermuk, 170km southeast of Yerevan, has been on our ‘must-visit’ list for a few years. Not because we wanted to sample the town’s famous mineral water (nice when drunk from the bottle, i.e. processed, but a bit weird straight from the source!) or hike to the town’s 72-metre waterfall (impossible anyway, given the amount of snow we encountered!) but rather because we were keen to have a poke around the remains of the abandoned former Palace of Culture, and also see what other interesting Soviet-era relics we could find.

During Soviet times, Jermuk established itself as a popular destination for medical tourism for nationals from all over the Union. This was mainly down to the therapeutic powers of the town’s mineral springs but visitors were also attracted by the alpine scenery, hillside geysers and prospect of plentiful fresh air. From the early 1960s onwards several sanatoriums were established, along with boarding houses and other infrastructure, to accommodate the influx of tourists arriving in Jermuk for medical treatment and recreational activities. Even a small airport served the town which, up until 1989, received up to four 24-27 seater Yak-40s per day (anything larger would have struggled with the complications of landing in mountainous terrain).

For several decades, Jermuk prospered as a resort town but this all changed after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991 and the subsequent post-independence economic crisis that hit Armenia thereafter. Visitor numbers declined, construction work came to a standstill and the airport ceased functioning (*). A population of around 10,000 inhabitants in the late 1980s dropped to less than 5,000 by the early years of the 21st century.

(*) There is an insightful article in the online magazine, Urbanista about the fate of Jermuk’s airport and its employees. It inspired us to try and visit the airport during our time in Jermuk but we couldn’t find transport willing to take us and the snow prevented us from getting there on foot as the only option would have been to walk along a busy truck-ladened road with limited options for getting out of their way.

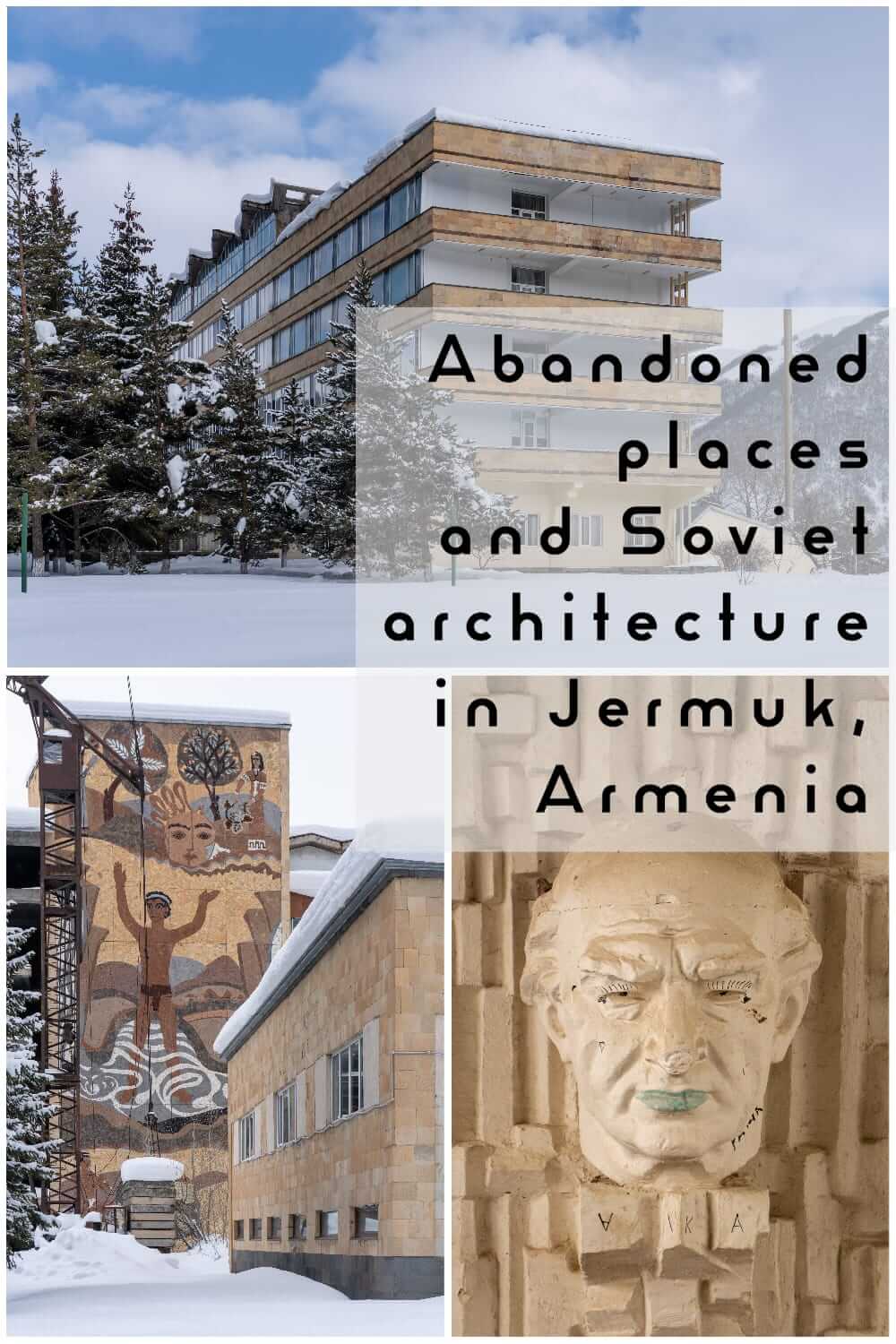

Jump to the present day and Jermuk is seeing a revival as a medical and recreational tourist destination – new hotels and health centres have opened in recent years and sanatoriums that saw a decline in visitors during the turbulent post-Soviet years are once more busy with bookings. But, there are still a handful of buildings in Jermuk from the Soviet era that either remain closed or are completely abandoned. The most prominent of these is the town’s former sports and cultural centre.

The former Palace of Culture in Jermuk

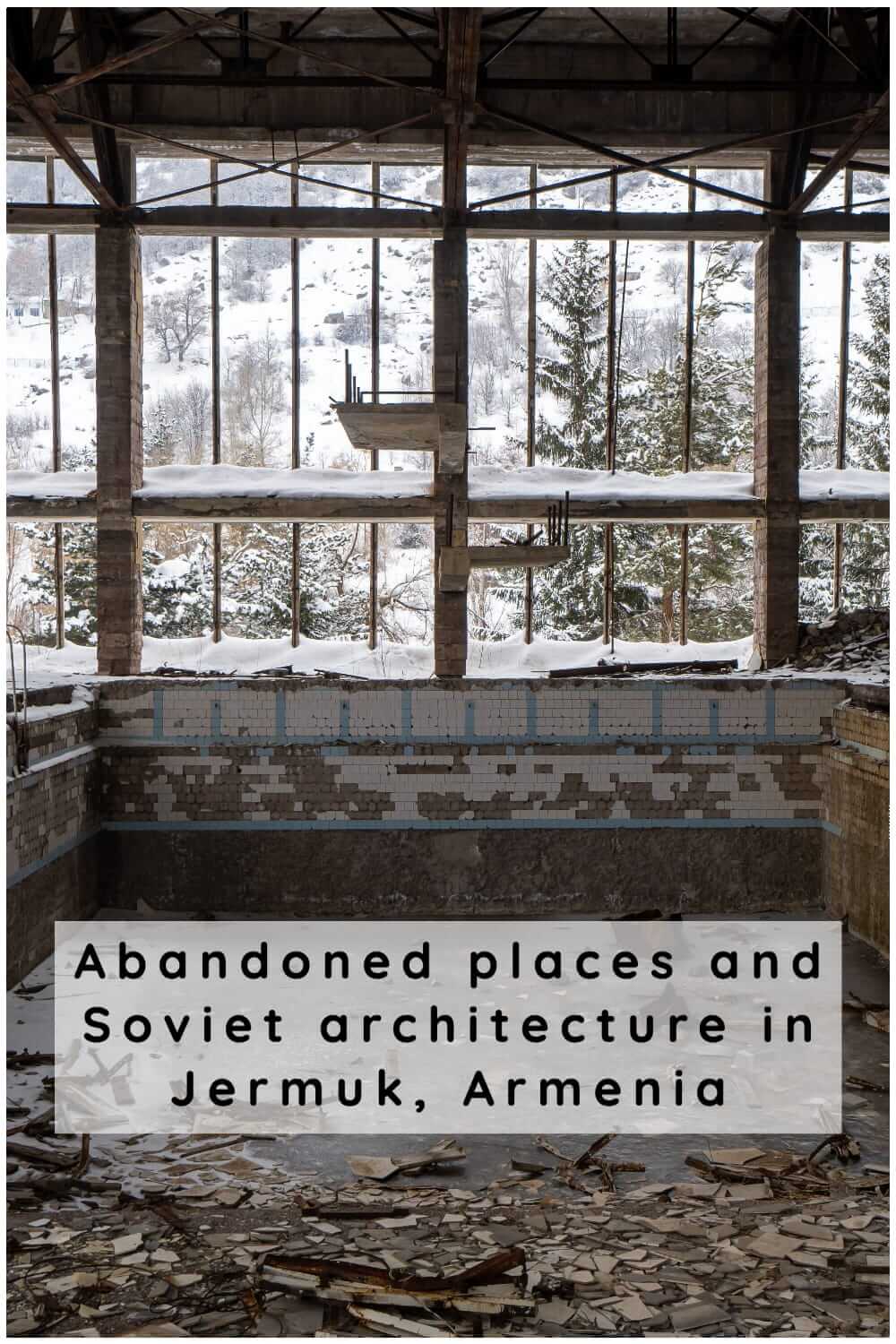

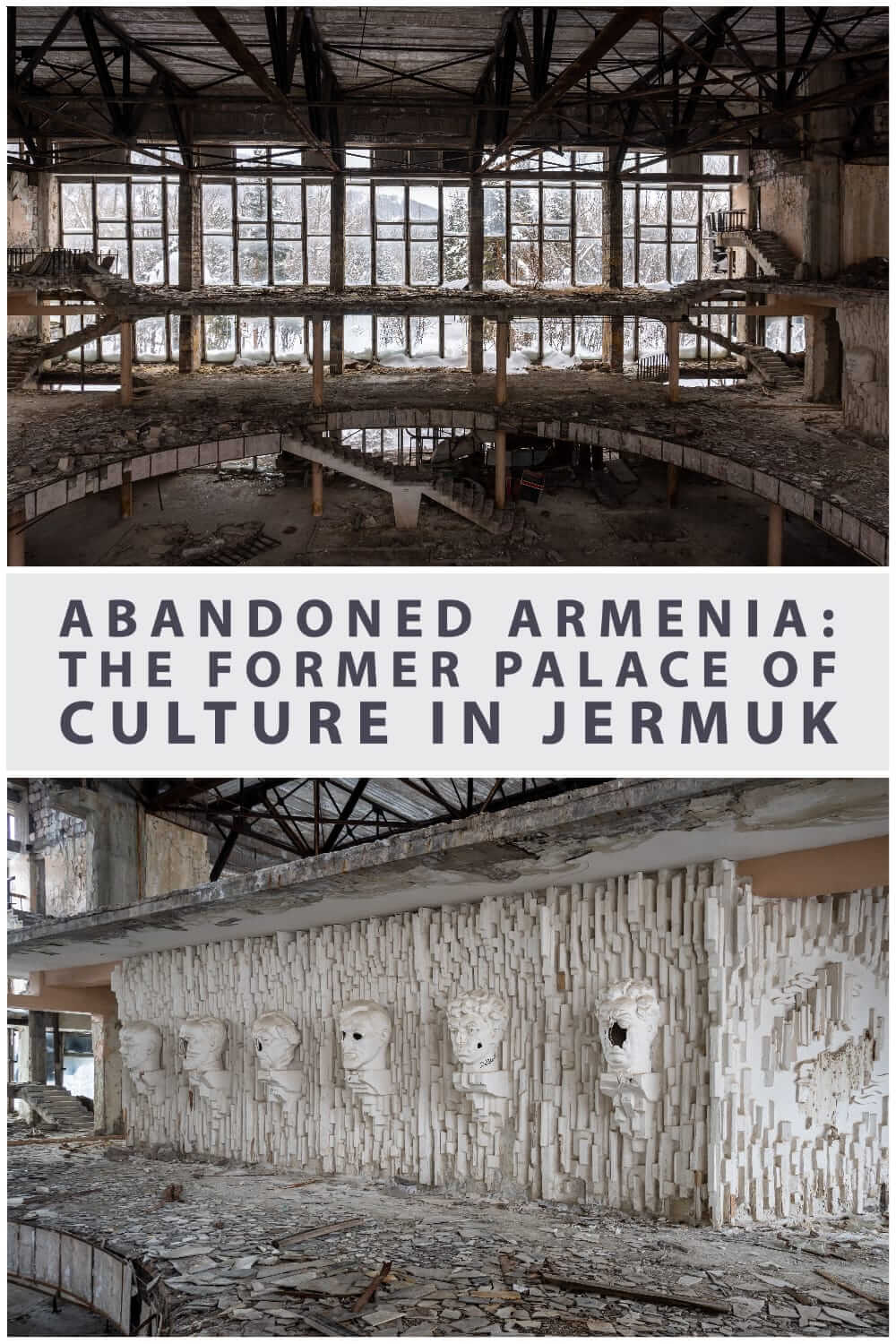

Stretching along the southern bank of Sarnaghbyur Lake, about 500 metres east of the Mineral Water Gallery, the town’s most renowned landmark, the Palace of Culture in Jermuk is a large affair designed in classic Soviet modernism style. The construction of the building started in 1969 but, for reasons I cannot discover, was not completed until 1986. The building was presumably a victim of the breakup of the USSR and is why it fell into a state of disrepair but as to when this happened is also something I can’t determine. Did it only function as a sport and cultural centre for a handful of years (1986 until 1991?) and then rapidly fall into decline, or did it continue to receive visitors after the breakup of the USSR and eventually get into the dilapidated state it is in today?

As is apparent from our photos, we visited Jermuk in the depth of winter and the snowfall was very heavy indeed. In fact, neither Kirsty nor I have experienced snow this deep before and, although the track leading to the Palace of Culture was OK for walking along, once we arrived and were looking for a way in we were temporarily flummoxed and didn’t know what to do. Under normal circumstances entering the place is a piece of cake – there is nothing to climb and all the glass has gone from the ground level of the floor-to-ceiling windows so it’s a matter of avoiding the shrubbery and simply waltzing in. However, the snow was so deep that a route in so obvious. After a few minutes of scratching our noddles and surveying the lie of the land, we picked a spot and slowly waded through knee-deep virgin snow until we had made our way inside.

The first thing to grab your attention when you enter the building’s large central atrium is the remains of six busts mounted on a decorative wall on the next level up. We’d heard rumours that these casts of Soviet writers and other artists that eerily adorn the interior of the Culture Palace had been destroyed but, although they weren’t in especially good condition, they were still there so we gave them our attention before exploring elsewhere. UPDATE: we have now been told by a reader who visited in November 2023 that, sadly, the busts are now completely destroyed.

When it was completed, facilities inside the Palace of Culture included a swimming pool, a library, an 800-seat theatre/lecture hall and a cafe. We managed to see the remains of all of these as we quietly wandered from one part of the complex to the next. While climbing one of the once-sweeping staircases, we heard a noise that we didn’t make. We then noticed a pack of four dogs on the opposite side from what we were on. Thankfully, they were more concerned with huddling together and keeping warm than what we were up to so we steered clear of them and they kept away from us. They can just about be seen by the central window in the bottom left photo.

What we didn’t manage to do, however, was get up onto the roof of the building. The blueprint for the Palace of Culture included a rooftop terrace which featured an outdoor swimming pool, sun decks and a movie theatre. By all accounts, the terrace was also heated so it could be used all year round. We searched for a way to get up there but to no avail but can confirm the existence of the terrace and its facilities as a friend of ours did get onto the roof and sent us a few photos of what was up there.

As for the fate of the now-very dilapidated Palace of Culture in Jermuk, that is a question to which I don’t have the answer. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, the structure was purchased by an Armenian businessman who vowed to restore it. But, he ran into financial difficulties and the project never got off the ground so, for the foreseeable future, the building just sits there, decaying even more year on year.

Other Soviet-era architecture and relics in Jermuk

There are several Soviet-era sanatoriums in Jermuk that are worth checking out. They range in style from Stalin-Empire architecture to Soviet modernism. We also came across an abandoned theatre, a few monuments and memorials, and a well-preserved mosaic/mural on the side of an unfinished building.

Map of locations in Jermuk, including the Palace of Culture

Jermuk Architecture

Olympia Sanatorium

An example of Stalin-Empire style architecture, the Olympia is one of the oldest sanatoriums in Jermuk. The fountain out front, which we could only see the top half of because of the depth of the snow, is titled ‘Dancing Girls’ and was added in 1978.

Ararat Mother and Child Sanatorium

Dating from the late ‘70s, the Ararat Mother and Child Sanatorium was full when we walked in to enquire about signing up for a health package. We lingered for a bit, however, as it was nice and warm compared to the bitter cold we had to return to!

Ashkharh Sanatorium

The Ashkharh is another 1970s sanatorium. The impressive artwork to the left of the sanatorium is attached to what was intended to be a cinema but was never completed. Hence the rusty crane in the foreground.

Gladzor Sanatorium

Completed in 1986, Gladzor was most likely the last major sanatorium to be built in Jermuk. We spent ages trudging through the snow to get to the entrance of Gladzor Sanatorium as we had seen a YouTube video of the abandoned interior and some particularly fine stained glassed windows, which we were keen to see. The building was most definitely still abandoned but we could see a couple of vehicles outside and, as we got closer, men humping stuff into them. They turned out to be contractors rather than looters and they told us the property was currently being renovated. We asked about the stained glassed windows and they confirmed they were still in situ but gave us a resounding ‘no’ when we asked if we could go inside and see them. The deep snow stopped us from taking a more discreet route to try and enter without being seen!

Former theatre

Built using the distinctive pink tufa rock that can be seen in many towns and cities across Armenia, Jermuk’s theatre most likely dates from the 1950 or ‘60s. It’s now abandoned and was yet another building that we couldn’t take a closer look at because of the snow!

Monuments and memorials in Jermuk

Monument to the 50th Anniversary of the (1917) October Revolution

Called October 50 on Google Maps, the monument is bang in the centre of town and was erected in 1967 (funny that!).

Heroes Alley

Heroes Alley is located on the opposite bank of the Sarnaghbyur Lake, overlooking the back of the former Palace of Culture. Also known as the sculpture group of the Armenian faithful, the pathway is lined with busts of seven members of the Armenian fedayi, a band of irregular fighters who were active in Armenia during the late 19th and early 20th centuries when the country was under Ottoman rule. Their main objective was to protect Armenian villagers from being murdered and/or pillaged by Turkish forces, Kurdish gangs and criminals in general but they also went about sabotaging the activities of the Ottomans in regions populated by Armenians. Armenian fedayi were often active members, or leaders, of the Armenian liberation national movement, a political and military organisation which was at its zenith during World War I and had the ultimate goal of creating an Armenian state.

All seven statues, six male and one female, were carved from basalt and were the work of the same Armenian sculptor, Hovhannes Muradyan. They were created between 1988 and 1992. There is an information plaque next to each one, which we didn’t know about at the time because, yep you guessed it, they were covered in snow!

Monument to Israel Ori

Israel Ori was also a leading figure in the Armenian liberation national movement, but much earlier around the end of the 17th and beginning of the 18th century. This monument was created in 2004 and is located on the approach to Jermuk, just before the bridge that crosses the Arpa River. There are fine views of the Gladzor Sanatorium from nearby the monument, plus it is near one of the main routes down to Jermuk waterfall.

Memorial to the Victims of the Nagorno-Karabakh War

This memorial is associated with the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (February 1988 – May 1994) rather than the more recent Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, which took place in the latter part of 2020. The memorial was probably created in the mid-to-late 1990s and is a short walk out of town, close to the Jermuk Ropeway car station.

How to get to Jermuk on public transport

The easiest way to get to and from Jermuk is on a marshrutka (fixed route minivan) from Yerevan. They depart/arrive from this point in Yerevan (GPS; 40.141682, 44.494665), which is a short walk from Gortsaranayin metro station. In Jermuk, marshrutkas depart and arrive from outside the Monument to the 50th Anniversary of the October Revolution. The journey time between the two destinations is approximately 2½ to 3 hours.

Because we like to break journeys and visit random places we spent the night in the small town of Yeghegnadzor en route from Yerevan to Jermuk. Yeghegnadzor is around 45kms from Jermuk and is located just off the main highway leading south from Yerevan to Gori and beyond to the border with Iran. Getting public transport to Yeghegnadzor from Yerevan was no problem as the Jermuk-bound marshrutka dropped us off. But, we couldn’t find any onward transport to Jermuk from Yeghegnadzor the next day and so we had to take a taxi. This cost us 6,000 Armenian Dram (about $11/£9).

Leaving Jermuk for Yerevan, the public transport options were very obvious. We asked around and established a daily marshrutka to Yerevan leaving at 7.45am. The cost was 2,000 dram per person. There are also shared taxis running this route and we recommend asking around for a telephone number if you want to take this option.

Where to stay in Jermuk

The combination of heavy winter conditions and COVID restrictions meant that many of Jermuk’s hotels were closed during our visit. In more normal times, there is a good range of places to stay from simple guest houses to fancier options like the Grand Resort Jermuk or the Jermuk Hotel & Spa.

More posts you might like to read

If you enjoyed reading about the abandoned Culture Palace in Jermuk, pin it to your related boards

Witnessing the present condition of the former Palace of Culture in Jermuk is very saddening. Why is the Armenian government not interested in restoring it? Is it because of the economic crisis?

It is very sad. Unfortunately, I think the lack of available funding is a major reason these old buildings aren’t maintained or restored.

In Soviet times, Jermuk was famous for its health resorts and mineral water factories which attracted not only Armenians but also the guests from different foreign countries

You are correct. Hopefully you learnt that and more from reading our post 😉

Amazing photos from inside the former Palace of Culture! Do you know if it’s still like this – as in the photos – today?

Thank you for the compliment, Thomas. I believe it is still like this inside. We visited just over a year ago.

I visited the building two days ago, and to my deep sadness, the busts of the artists are completely gone 🙁

Hello Alberto, thank you for your comment, although it is indeed sad news. We will update the post to reflect this. Regards, Mark

Being on a Trip through Armenia we spent two days in Jermuk (August 2024). You can just walk inside the former palace. Sad to see. Our Guide told us, she used to go dancing in the former theatre. We didnt try to have a look inside. There seems to be some construction at the Glazdor, but it’s still closed.

Hello Christina, thank you for the update following your trip to Jermuk. It seems that the ongoing work at the Glazdor Hotel is going to be a slow process!

Revently visited in Oct 2024. You can enter easily via the side road next to the hotel. Looks largely unchanged from your photos with the exception of the damaged busts, as mentioned by Alberto. A very thought-provoking place.

Hello Matt, thank you for taking the time to send an update on the condition of the building. Regards, Mark