And on becoming Architect Tourists …

What is a Palace of the Pioneers?

Take what we commonly call a Youth Centre, supersize it and give it a Soviet makeover and voilà, you have the Palace of the Pioneers.

Like the Scouts, the Pioneer movement was set up as an organisation for children. Indeed, the movement was modelled on Robert Baden-Powell’s original concept but unlike the Scouts, which is independent of political control, the Pioneer movement (which originated in the Soviet Union and didn’t extend beyond communist-controlled countries) was funded by the government (and sometimes trade unions) and as a result, there was as much emphasis on political education as there was on attributes such as physical and mental well-being.

Not surprisingly, those opposed to communism accused the movement of being a form of indoctrination but, for a time, it was incredibly popular with children between the ages of 10 and 15 in communist-controlled countries. Joining the Young Pioneers in the Soviet Union, for example, was not compulsory but it was free and offered numerous benefits, not least the opportunity to get out and about in a country where movement was restricted (many Young Pioneer Camps, aka summer camps, were created around the same time).

As for the palaces themselves, they date back to the 1920s, when the newly formed Government of the Soviet Union (established in 1922) nationalised many of the vast palaces and stately homes that previously belonged to the elite of the Russian Empire. But the first official Young Pioneer Palace in the USSR was established in Kharkiv (Eastern Ukraine) in 1935. It was housed in a building that originally belonged to the Assembly of the Nobility, a self-governing body that looked after the affairs of the Russian gentry pre-1917 October Revolution. From what I can work out, the building still exists although we didn’t try to locate it on our recent visit to Kharkiv (August 2017). Instead, we went looking for its far more Soviet-looking replacement, the Palace of Children and Youth Creativity, which was built in 1993. Upon seeing it, both Kirsty and I concluded that it was a rather unfortunate design given its association with children!

By 1971, there were in the region of 3,500 Pioneer Palaces in the USSR alone but after its breakup in 1991, many of them were closed down and those that did remain, or reopened as Youth Centres began to charge admission and their popularity declined. The Pioneer organisation still exists today but membership is way smaller than it used to be and they no longer compete with the Scouts as an important international youth movement.

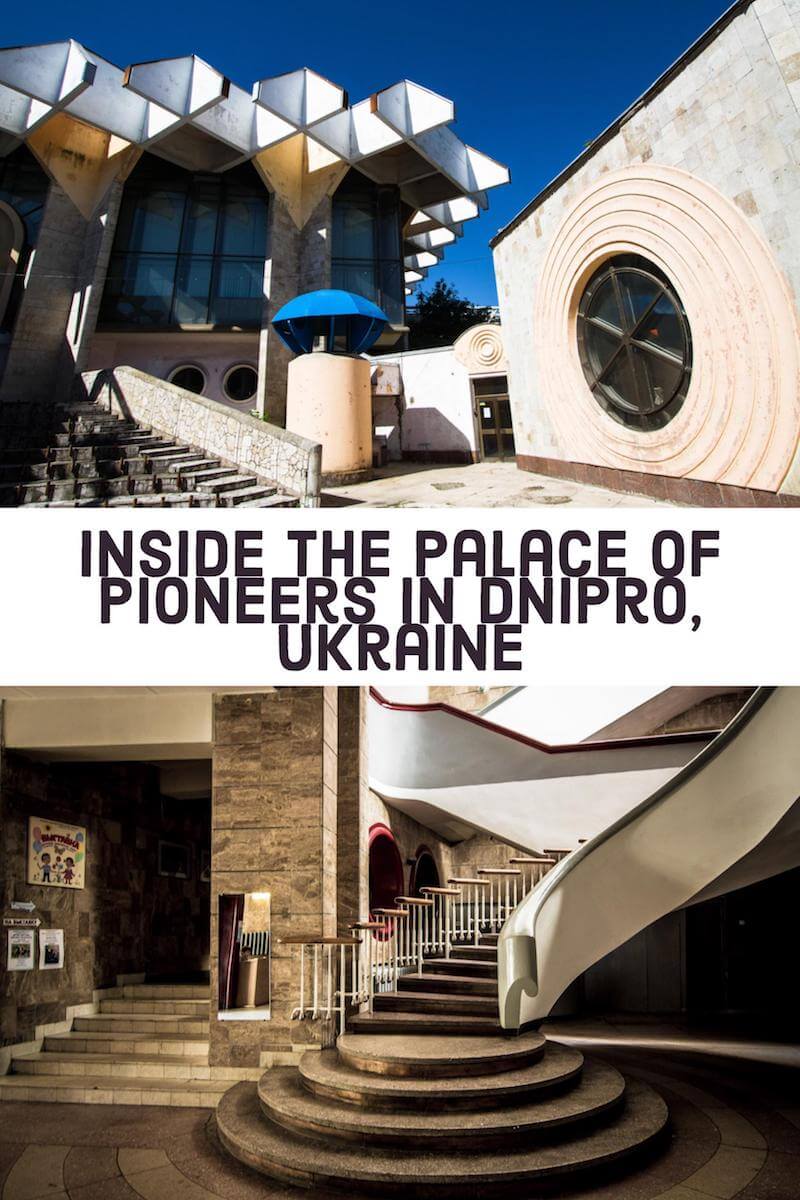

The Palace of Pioneers in Dnipro

With their futuristic shapes and classic Soviet-era designs, architecturally, we find Pioneer Palaces very interesting but we haven’t managed to see that many during our travels in this part of the world. They aren’t as easy to research and track down as Soviet-era wedding palaces or circuses are for example and we don’t come across them that often.

Apart from the one in Kharkiv, we’ve seen the Pioneer Palaces in both Kyiv and Lviv (The Centre for Culture and Creativity for Children and Youth) as well the one in Almaty, Kazakhstan (now renamed the Republican School Children’s Palace). But we’ve always had to be content with just looking from the outside and it wasn’t until we went to Dnipro * (formerly Dnipropetrovsk), Ukraine’s fourth-largest city, that we had the opportunity to explore one in a little more detail.

(*) Pronounced with both the D and the N but the N dominates.

Dnipro is a strange city that we have written about in more detail here. On the one hand, it is extremely run down and darn right depressing in parts, while on the other there is a vibrancy about the place that makes it a very liveable city indeed. We spent four days there as part of our recent six-week trip around Ukraine (July/August 2017) and wandered around the city for hours on end looking for the weird and wonderful, people-watching and being shouted at for photographing things we probably shouldn’t have been photographing!

One instance when we were out with the camera and thought we were in for a good old-fashioned Soviet-style bollocking was when we visited Dnipro’s Palace of Pioneers. Located a little away from the centre of the city and also known as the Palace of Children and Youth, we were round the back of the building, taking a few snaps, when this guy spotted us and ambled over. “Here we go,” we thought. “It’s narky shooing- away time again,” but this guy greeted us and asked if we were “архітектор туристичний (architect tourists)”. Architect tourists, we mused, that’s a good way to describe us and replied with an enthusiastic da, da!

A recurring theme for us when visiting Ukraine is a severe lack of communication with Ukrainians. Apart from China (*), it is probably the country in which we have the hardest time language-wise.

(*) I recall my first visit to China in 1991 as if it were yesterday. Arriving at Shenzhen’s main station from Hong Kong and trying to get an onward ticket to Guangzhou was one of the most daunting experiences I have ever had. It’s not as bad these days as the younger Chinese are hungry to learn (and practice) the English language but it can still be hard work if you get away from the main cities and come into contact with the older generation.

Of course, this is our failing, not theirs (*). We speak about ten words of Ukrainian (mostly food and alcohol-related!) and about the same again when it comes to Russian. Quite a few Ukrainians speak German but, once more, we don’t so we rely on physical gestures (my favourite is asking for the train station – left arm up (choo, choo!), followed by both arms by my side (chooga, chooga, chooga, chooga!) – it always gets a laugh (and a raised eyebrow from Kirsty!)). Alternatively, or as well, we also rely on Google translate if we have access to the internet.

(*) Without a hint of irony, I argue that, as a native English speaker, it is not my fault that I don’t speak another language. I do genuinely envy people that can converse in more than one language and have the ability to learn them. But, from my experience, there aren’t many places in the world where you won’t find at least one person who can speak a smidgen of English (often or not this is a child) and it’s almost always possible to get your point across with a few keywords accompanied by some animated gestures. And the number of people worldwide who will be able to communicate at some level in English will only increase with time. The Chinese are a prime example of a nation keen to grasp our vernacular and even in Ukraine these days, English is now taught as the second language rather than Russian. And that, in a nutshell, is why I (and many other native English speakers) am all but useless when it comes to other languages …

Our encounter with this guy, whom we soon discovered was called Vladimir, was typical of our interaction with most Ukrainians. After confirming we were architect tourists, he asked us where we were from and whether we spoke Ukrainian. We both always reply in unison when we get asked this question with a resounding nyet, to which we add another one a couple of seconds later when asked if we speak Russian. Sometimes we even have to add a third nyet when asked if we Sprechen sie Deutsch? Either way, we get the message across pretty quickly that communication is going to be a problem. But here’s the thing, and it makes me smile every time it happens, two or three nyets in quick succession do not deter Ukrainians from carrying on their conversation with you. They don’t slow down or speak the Ukrainian equivalent of pidgin English but instead rabbit on at full speed. We both smile a lot. I nod as if I have the remotest clue what the person (or persons) in front of me is talking about and Kirsty (whose ability with languages outstrips mine at least tenfold) tries to catch the odd word and piece together what is being said. Ukrainians are friendly people and they often try to help us and by persevering (read Kirsty here!), we normally get the help/information we are looking for.

Vladimir (pictured below) wasn’t helping us per se but as we stood around the back of the Palace of the Pioneers in Dnipro, he was talking at us ten to the dozen about the building and no doubt telling us all sorts of interesting facts about it. He worked there, that much we understood, and described himself as an engineer. He had visited London once during Soviet times on an exchange program and his daughter apparently spoke decent English.

The Palace of Pioneers (Palace of Children and Youth) in Dnipro

After about 15 minutes of getting acquainted, he asked us if we would like to see the interior of the palace. Another enthusiastic round of da, da, da’s from Kirsty and I confirmed that we would like to very much and we dutifully followed him inside. We waltzed past the ageing security guard (the type that normally shoos us away from such buildings) as Vladimir explained that we were architect tourists (there it is again!) to anyone that was paying us any attention. He gave us a comprehensive tour, turning on lights, explaining things and allowing us to take as many photos as we liked. Eventually, we went back out into the sunlight, promised to stay in touch and said our goodbyes.

You might be wondering what the big deal is? So we got inside a glorified theatre but, for architect tourists like ourselves (have I mentioned that we are now officially architect tourists!) with an admiration for Soviet Modernism, this was kind of a big deal. As mentioned earlier, we spend much of our time marvelling at the outside of such buildings and wondering what they are like inside so to be able to poke around the interior of one was an interesting experience for us and we enjoyed it very much.

How to get to the Palace of Pioneers in Dnipro

If you want to visit the Palace of Pioneers in Dnipro, here’s what you need to know:

Name in Ukrainian: Палац дітей та юнацтва (it translates as Palace of Children and Youth)

Coordinates: 48.450482, 35.080381

Public transport: Take Trolleybus #12, which runs parallel to the river, and get off at Instytut fizkul’tury stop

And if you do visit and happen to bump into Vladimir, give him our regards.

And finally …

Excuse the quality of some of the interior shots. We don’t carry a tripod (too much weight) and although Vladimir turned on the lights in each section we entered, it was still quite dark and therefore hard to take photographs that were in focus.

SEE MORE BLOG POSTS ABOUT UKRAINE

VISIT ARCHITECTONIC FOR MORE BUILDINGS OF THE SAME GENRE

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS POST, PLEASE PIN IT…

I am also fascinated by these type of Soviet places….they are such an interesting part of history.

I agree. We were lucky to get invited in!

interesting article to read 🙂

Hahahaha, I’ve been laughing for 5 minutes at that Kharkiv picture. So glad you were able to track the place down.

The inside of Dnipro’s Pioneer Palace is majestic, I really dig it! Did Vladimir tell you what it’s being used for nowadays? It’s amazing that you and Kirsty have photographed so many of these unique buildings. Please keep it up!!

Yep, the Palace of Children and Youth Creativity in Kharkiv is an unfortunate design, that’s for sure! From what we could gather (our Ukrainian and Russian is very limited!), the Pioneer Palace in Dnipro is being used these days as a youth centre and also a theatre. It was the middle of the day when we visited and therefore pretty quiet but, it looked like performances were still being put on and the place was in pretty good condition inside. It was certainly being used for something, which we were pleased about!

We are on a mission to track down and photograph as many of these Soviet-era buildings as we can. Not just in Ukraine, but the rest of the former USSR and also eastern Europe. Many are being (understandably) demolished so we are up against time somewhat but slowly we hope to get there!