Visiting Sarajevo’s abandoned Olympic sites

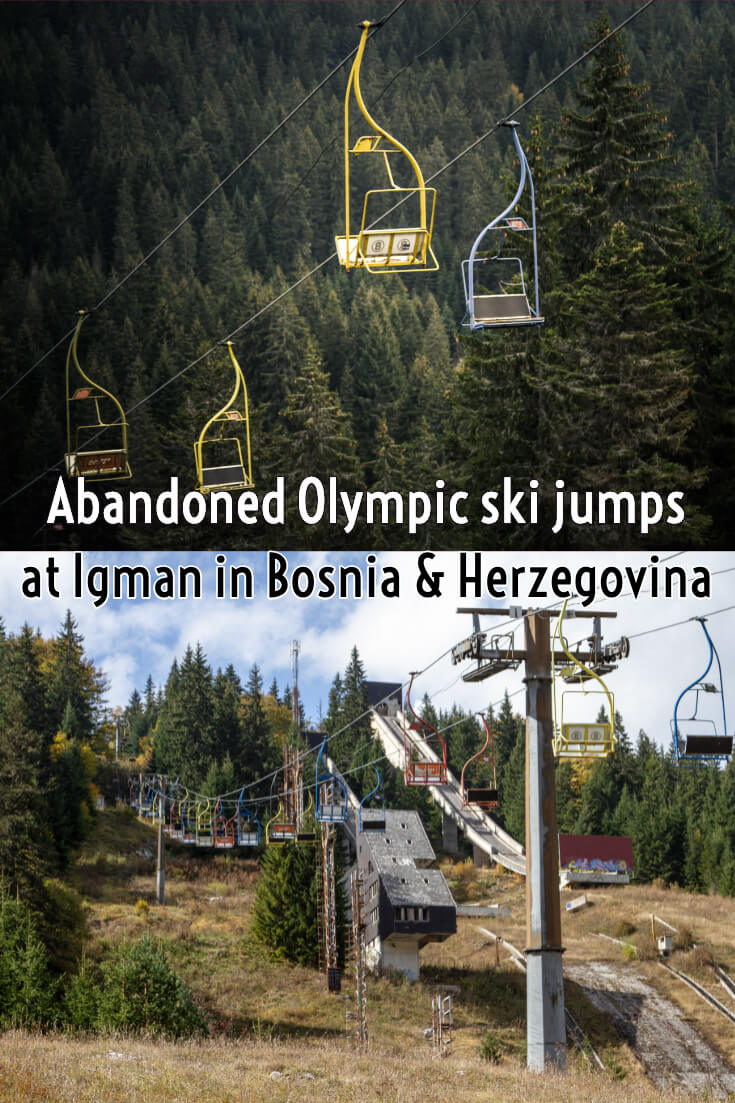

The now-abandoned ski jumps and nearby Hotel Igman were constructed in the early 1980s in preparation for the 1984 Winter Olympics which were hosted by the nearby city of Sarajevo.

Igman, also known as Malo Polje (small field), is a mountain plateau and, during the Games, it was used exclusively for Nordic Olympic events (cross-country skiing, ski jumping and Nordic-combined, in which athletes compete in both of the other two sports) during the Winter Games.

The former Olympic venue is approximately 30km southwest of the centre of Sarajevo and 25km from the city’s international airport.

As part of the preparation for the ‘84 Olympics, a new road was constructed that linked the plateau with Sarajevo airport.

The complex was destroyed during the Siege of Sarajevo (part of the War in Bosnia), which began in April 1992 and lasted until February 1996.

I appreciate this is a rather factual start to a blog post but, this information, coupled with what I’m about to describe below, sets the scene and helps to unravel why, not even a decade after its construction, this expansive Olympic venue now lies in tatters.

First, a bit of history

I spend a lot of time reading and watching documentaries about the wars in Yugoslavia. I am particularly interested in the topic but I also find it incredibly confusing at times. There is no doubt that it is one of the most complex series of military campaigns in European history (and there’s been a few). What’s more, given the timeline, it is also one of the most sensitive conflicts of recent times and, as a result, and even though I do my utmost to get my head around the subject, I’m often apprehensive to put pen to paper in case some of my facts are perceived to be incorrect. But, in order to continue writing about the Olympic sites in and around Sarajevo, it’s necessary to provide a little background information, so here it goes …

There were basically four primary military sides involved in the Bosnian War (*).

(*) For the sake of simplicity, I am considering the United Nations and NATO as one side.

On the one hand, there was the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (ARBiH) or, more commonly, the Bosnian Army. This army was newly formed in 1992 by the Bosnian government in response to the outbreak of the war. The ARBiH were predominately fighting the Army of Republika Srpska (*), also called the Bosnian Serb Army (BSA). This army was also established in 1992, with many thousands of its soldiers being drawn from the original Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA), which was disbanded in the same year.

(*) In brief, Republika Srpska (literally Serb Republic) is one of two entities within Bosnia and Herzegovina, with the other being the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The population of Republika Srpska is predominantly Serb in ethnicity and its claim as a sovereign state in the early 1990s, which was not recognised by the Bosnian government, was one of the major causes of the War in Bosnia.

Parts of the region around Igman were under the control of the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, while others areas were held by the Bosnian Serb army.

The other Balkan faction embroiled in the Bosnian War was the Bosnian Croats but, as far as I can make out, they were not involved in the fighting around Igman and so won’t be mentioned again in this post.

The final armed force involved in the War in Bosnia was the United Nation’s Protection Force (UNPROFOR). Comprised of close to 40,000 troops from forty-two different countries, UNPROFOR’s role in the war was one of peacekeeping and humanitarian aid. They were supported by NATO, whose original task was to initiate a lasting peace in the region but who also ended up providing military intervention in the form of ground and air attacks.

Sarajevo airport, which had been upgraded for the 1984 Winter Olympics, was under the control of the United Nations.

There is one more important element to throw into the mix. By June 1993, there was an operational tunnel (known as the Sarajevo Tunnel) connecting Bosnian-held territory very close to the airport with the blockaded city itself. This lifeline, 340 metres of which ran under the airport runway, played an essential part in supplying those stranded in the city with basic necessities such as food and clothing. It was also used to ferry military equipment into the city for those members of the ARBiH defending it from within.

All of the components above meant that very early on in the war, Igman, and especially the highway connecting it with Sarajevo airport, became an area of vital military and strategic importance to all involved parties. It didn’t take the BSA long to figure out that the road was being used as a supply route by the ARBiH for the besieged city of Sarajevo. Fighting intensified and the BSA gained territory after a major offensive in the summer of 1993. It was only the threat of NATO airstrikes that halted their advancement even further and, eventually, the area around Igman was declared a safe or demilitarised zone (DMZ) by the United Nations.

A UN-backed treaty was brokered between the two sides and it was decreed that the road could be used but only for humanitarian aid not for transporting military supplies. As part of the pact, UNPROFOR troops were stationed in the buffer zones.

Neither army was keen on the ceasefire. The ARBiH clearly still needed the route to get weaponry and other military supplies to the tunnel and eventually into Sarajevo itself, while Ratko Mladić, the notorious warlord and leader of the BSA (now serving a life sentence for genocide and war crimes), was eager to capitalise on his side’s recent advancements. Violations of the safe zone, which developed into another all-out-attack by the BSA in August 1995, were part-responsible for UNPROFOR and NATO’s soon-after decision to implement Operation Deliberate Force, a series of airstrikes in conjunction with ground operations that purposely attacked BSA strategic targets.

The airstrikes, in the region of three hundred in total, lasted until the middle of September 1995 and resulted in the BSA withdrawing their heavy artillery from the exclusion zone surrounding Sarajevo and thus beginning the process of ending the longest siege of a capital city in modern-day military history.

During the course of the War in Bosnia, the route linking the location of the 1984 Winter Olympics with Sarajevo’s international airport was, not surprisingly, often referred to as the most dangerous road in Europe.

As an aside, and a final commentary before I move on to our personal experience of visiting the area, the ground forces deployed in the Igman region as part of Operation Deliberate Force consisted of British, French and Dutch troops. The British unit was the 19th Regiment Royal Artillery and not long after our visit, I posted a photograph of the Hotel Igman in one of the Facebook groups I’m a member of that appreciates brutalist architecture. It received a few comments, including one from a guy who said his brother was a British soldier in Bosnia during the conflict and, for some of the time he was stationed at the Hotel Igman. I managed to make contact with the brother and explained to him that I intended to write about the hotel and the remains of the Olympic complex and would he be interested in being interviewed or contributing anything he was willing to share about that time. He said he would but, unfortunately, he must have either changed his mind or forgotten about it because I didn’t hear from him again despite a polite nudge from me.

I did find out, however, that he commanded an artillery unit and he recalled, “We had a field medical station in the underground car park (of the hotel) and treated the place as you’d expect. If walls needed to go, they went. My Land Rover was parked inside on the ground floor just behind the graffiti.”

I would have loved to have found out more and maybe added some of his photos to this post but I didn’t want to push it. Who knows, maybe he will read this and be prompted to make contact?

Our visit to the Olympic ski jumps and former Hotel Igman

When we arrived in the Igman area, we first stopped to explore the hotel. As you would imagine with a property that has been ravaged by war, there wasn’t a whole lot to see within the building’s interior. We were alone during our visit but the odd splodge of paint on the walls as well as old rubber tyres here and there gave away the fact that the place was sometimes used as a paint-balling location. We made our way to the roof where the views of the surrounding mountains were mighty fine, but it was really the exterior of this brutalist hotel that was the highlight and we spent quite some time admiring and photographing its harsh contours before returning to the car and continuing to what is left of the 1984 Olympic complex.

The difference between the two locations was quite a contrast. Just 5km separates them but, the remains of the Olympic venue, which is also dominated by large pieces of abandoned concrete in the form of two ski jumps and a judge’s tower, had one thing that the hotel didn’t and that was other people.

There were several cars in the carpark when we arrived and, on the grassy verge at the bottom of the ski slopes, we saw families playing games and picnicking. We were a bit surprised by this, but it was a pleasant surprise nonetheless and nobody was there to stop us taking a closer look at the two jumps and the judging tower with its distinctive UN sign plastered on the side.

It was a steep walk up to the bottom of the jumps and, once there, the option was either to walk through the undergrowth to the back side of them and use one of the two staircases that lead to the top or clamber directly up the concrete slopes themselves. We chose the former but did watch a couple of fearless people walk straight up one of the jumps and it was at this point that we decided that anyone who did ski jumping through choice wasn’t quite right in the head!

What’s to become of the remainder of the Olympic complex is uncertain but I’m glad it’s being used as a place of recreation and fun. When we left, we followed the infamous road all the way to Sarajevo airport, all the while pondering how anxiety-ridden it must have been to have driven along it during the height of the war.

How to get to the Olympic ski jumps and former Hotel Igman

We visited Igman in October 2018 as part of our last Balkan road trip. From what I can gather, there are no public buses linking Sarajevo with Igman. The only option is to have your own transport, hire a taxi or join a tour. A quick search on TripAdvisor revealed companies that include the area on their itineraries, plus the small but helpful tourist board in Sarajevo’s Baščaršija (Old Town) (GPS 43.858953, 18.431037) should also be able to help with recommendations.

READ MORE BLOG POSTS FEATURING THE BALKANS

WHY NOT PIN THIS POST TO YOUR TRAVEL OR ABANDONED PLACES BOARDS?

Fabulous pictures Kirsty! The thing that gets me; after a massive financial and time and energy investment, all goes to ruins. I have seen this in other nations, sans wars or dramatic political changes. Father Time, I guess, plus the war and reasons you note. Everything eventually changes.

Indeed. We’re in Tunisia at the moment and it’s so sad seeing all of the deserted hotels along the coast.

It’s such a hard job (maybe it’s impossible?) to give an unbiased account on this war, It’s great to see you took to time to explain what’s behind this area. I’ve seen a lot of people going there just to get instagrammable pics, without understanding the complex history.

Thanks for commenting and you are correct, it’s very hard to simply portray the facts in, not just the Bosnian War, but all of the Yugoslavia Wars. As I said in the post, it’s one of the most complicated military conflicts in European history!

Great report! I visited the ski-jump which was amazing (and also the bobsleigh track) and went past the hotel not realising what it was or how safe/dangerous it was. I’d love to go back. Really interesting to see your pics from there.

Thank you! Yes, the hotel is rather out on a limb and it’s not obvious that it is connected to the ski-jumps. It wasn’t actually that interesting inside but the view from the roof was worth the climb up and the structure itself is a wonderful example of brutalist architecture and looks great from a distance. We’ve also been to the bobsleigh track but haven’t got around to writing about it yet. One day soon I hope!!

Very nice review of demolished and abondend Igman venue hosting Olimpic games in 1984. Brutalist architecture movement in Yugoslavia has given some both beautiful and brutally monumental buildings.

Old Igman hotel was very interesting and actually pretty sight. Star wars style in Igman.

Besides, I must admire your take on Yugoslav wars. You managed to pick historical narative that avoids pitfalls and millions of open questions.

Small fixes, Bosnia and Herzegovina is not a republic today. It’s a country formed by two equaly autonomous entities, Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Republic of Srpska (Serb Republic).

Also there was a 3rd big side in Bosnian war, Bosnian Croatian. War ended by uniting Bosniak and Croatian forces under NATO command against the Bosnian Serbs. Bosniak and Croatian parts of land merged into Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Reviewing Yugoslav wars outside of cold war context – war of Nato (and local proxies) vs Serbs / Russia, makes no sense.

Thank you for your valuable comments. I especially appreciate your remark about my take on the Yugoslav Wars. As I said in the post, I am always hesitant to put pen to paper as the subject is a very complex one but it pleases me to know I did a half-decent job!

I also appreciate your feedback on my facts. You are of course right that Bosnia and Herzegovina is no longer a republic. I will update the post accordingly. Regarding the Bosnian Croats, I was aware of their participation in the Bosnian War (I talk about the fact in this post about the Sniper Tower in Mostar https://www.kathmanduandbeyond.com/sniper-tower-mostar-bosnia-herzegovina/) but I guess I didn’t mention them in this post because they weren’t involved in what happened in and around Igman. Am I right on this fact, I will happily stand corrected if this is not the case but in all the stuff I’ve read about the fighting in and around Igman, there is no mention of the Bosnian Croats? What I should say in this post is that there were four factions involved in the Bosnian War (including NATO) but that only three were involved in the Igman conflict.

If you have time to reply to me on this I would appreciate your input as you clearly know your facts. I won’t update this section just yet in the hope of hearing from you once more. Cheers, Mark

Thank you for this article. We are visiting all these places today and it gives us the background story we were looking for!

You are welcome and it’s good to know the post has been helpful to you. Enjoy your visit!